“…Humanlike figures are squashed, tortured and consumed by roaming

brutes; piteous squawks and rattles pepper a soundtrack

soothed by Dan Wool’s moving musical score….” – New York Times

~~~

Across the nightmarish sequences and impressive stop-motion work

is a gentle score helmed by San Francisco composer Dan Wool. Mad God

may be a fever dream of bloody intestines, liquid feces, and rapid fire deaths,

but it achieves a hypnotic state thanks to its otherworldly score….” – Pitchfork.com

~~~

“…The score, from Dan Wool, is superb, which is handy given Mad God’s silent nature.

Wool’s work is a hypnotic and trance-inducing whirlpool of noise that almost acts as a calming

balm to the disturbing scenes on screen. If the pictures get too much, the viewer can shut

their eyes and still have a fantastic experience, Wool’s score taking them on a

beautifully rich aural journey all on its own. …” – The Hollywood News

~~~

“…somehow this black star also has one of the most beautiful scores of the year. Dan Wool

not only uses his tempestuous, tortured soundscape to translate the screams of Mad God

into a frightening, melodic banshee wail, but he also digs deep into Tippett’s

twilight nightmare, dredging up magic, illumination, and hope. ….” – Film Inquiry

~~~

“…Wool managed the impressive feat of composing music that never draws attention from

the visuals but that also stands alone as a visceral listening experience….” – The Film Scorer

~~~

“…Dan Wool’s score to this artistic vision is likely the best music to accompany a

film I have heard all year. As a standalone musical expression, movie aside, it

is one of my favourite releases to have been released this year. Dark, tender and

frail emotions combined with horror, panic, and the beauty of despair…” – The Grape Vinyl

~~~

“…Contrasting that ugliness is Dan Wool’s hauntingly beautiful score, a…mix

of guitars and synthetic sounds framing the horrible majesty on screen. …” – FOX 10 Phoenix

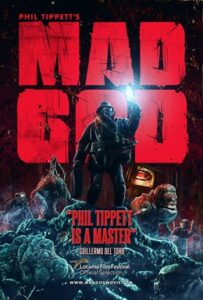

MAD GOD

Original underscore for independent feature film. Distributed by IFC Films. Vinyl and CD on Waxwork Records

Director Phil Tippett

Dan Wool’s Liner-notes from the double-vinyl album package. Waxwork Records:

“Want to check out this weird thing we’re working on?” was Phil Tippett’s initial pitch to me back in 2009 to see if I was interested in working on MAD GOD. I had met Phil through our mutual friend, filmmaker Alex Cox, while working on one of Alex’s films, and I soon realized that we had quite a bit in common in terms of our politics, and taste in art, music and films. I didn’t really know the scope of Phil’s work at the time, but I was familiar with his company TIPPETT STUDIO, a well regarded Bay Area visual-effects house. And surprisingly to me, Phil was familiar with a lot of my music, all the way back to my old band/film score-collective PRAY FOR RAIN.

“Want to check out this weird thing we’re working on?” was Phil Tippett’s initial pitch to me back in 2009 to see if I was interested in working on MAD GOD. I had met Phil through our mutual friend, filmmaker Alex Cox, while working on one of Alex’s films, and I soon realized that we had quite a bit in common in terms of our politics, and taste in art, music and films. I didn’t really know the scope of Phil’s work at the time, but I was familiar with his company TIPPETT STUDIO, a well regarded Bay Area visual-effects house. And surprisingly to me, Phil was familiar with a lot of my music, all the way back to my old band/film score-collective PRAY FOR RAIN.

One day Phil told me the story of how, while archiving film from some of his older projects, people at the studio had come across, and become enthralled with an old stop-motion short he’d started in the pre-CG 90’s, but never finished titled “MAD GOD”, and had volunteered to help him resurrect and complete the project. The first 9ish minute version I saw (although Phil remembers it as 3 minutes) was largely a study to see if the original film, he had shot on 35mm, could be cut together convincingly with newer digital stop-motion footage (it could), but even at that early stage MAD GOD had all the wonderfully insane and surreal qualities the finished film has today. It was a gorgeous and inspiring little piece with no dialogue – which meant lots of room for music! But the main reason I was keen to get involved was that Phil seemed eager and open to folding new ideas, the weirder the better, from anyone in the production team, into the MAD GOD experiment. A virtually unheard of quality for a director. Since there was no temp score I asked Phil what kind of music he had in mind and he just said “I dunno. Try stuff.” (I learned much later that this initial exercise was purely a test of my instincts). The film was short so I told him I’d try a few different directions and send demos of each as a way to triangulate on what worked for the film.

Once I had the video in my studio, I realized the piece, while chock full of meaty archetypal imagery, presented zero traditional cinematic points of reference to bite into and get started with. It felt dystopic, but not conventionally dark or scary. Drama and portent, and even humor was implied, but the narrative was wide open for the guessing. With no clear points of entry I decided to just do as Phil suggested and “try stuff”. The first pass was an awkward, rough sketch. Despite there being a lot of activity on the screen in places, I kept the initial ideas sparse, and ambient – I think with the intention of going back and filling in the spaces later. At this stage there wasn’t a sound designer for the project, and it wasn’t clear there would ever be one, so the demo included various, sort of, “musical sound-effects” created with musical instruments and synthesizers that stood in for sound design. Much of it placed in there just so I had sound to work to – I find it weird and lonely to try and write music to scenes that have no production-sound at all (being a stop-mo project there was none, of course). Creating the initial sketch gave me some specific ideas for the other two demos I was going to send, but thought it might be a good idea to test the waters with this initial outline to see if it was anywhere near what Phil wanted. As semi-presentable as it was I sent over the demo with a clear proviso that it really was just a rough sketch and that I’d be sending another pass soon. However, it wasn’t but a few hours later that Phil called and said “you nailed it”. “Thanks” I said, “but that was just a crappy preliminary sketch. I have another idea that’s going to be really great”. “No.” he insisted, “This is it’’. ….And that was it.

“MAD GOD is, by design, meant to invite the viewer to find their own dots to connect”

I managed to get Phil to agree to listen to the other demos I was 100% intending to send, but I got sucked into another project, and then another. A month or so later when I went back and listened to what I did, I thought “Hey, this is it”. As the film expanded I recalled and reapplied the same shoot-first-aim-later approach that worked so well for the demo to almost the entire scoring process. Of course with most films, the score plays a specific role to help cue the audience into the intentions of the filmmaker by using vernacular musical devices. But MAD GOD is, by design, meant to invite the viewer to find their own dots to connect, and extract their own meaning from the piece. Traditional musical devices could only inhibit that participation, so I steered away from ideas that leveraged those formulas overtly. I guess as an attempt to make sense of MAD GOD’s madness, the film is often lazily assigned to the Horror genre in the minds of some, but at no point did it occur to me or to anyone involved with the creation of MAD GOD, particularly Phil, to approach it as any type of genre-film. Any musical ideas that conspicuously suggested a particular genre wouldn’t have even made it out of the gate as I was writing the music. I didn’t always know what the score for MAD GOD should be exactly, but I always had a sense of what it shouldn’t be.

This isn’t to say the score for MAD GOD is without conventional musical approaches. There are themes and through-lines and the music does just what movie music is supposed to do in places, but most of the score is, simply put: a holistic response to the picture. This is exactly the approach I normally try to avoid with other films. I’m sure they teach on day-one of film score school (I imagine. I never went to film score school) to play to the subtext of the film, not necessarily to what’s on the screen. But MAD GOD even rejects formal subtext. Playing directly to my take on a subtext would make no sense, so…I responded. However, I learned almost immediately that the ink blots I was seeing in MAD GOD were entirely different than what others saw. At early screenings, I noticed people being completely freaked out by, and sometimes fleeing the theater during scenes I found beautiful and whimsical. On day-two of film score school, I bet they teach about counterpoint, the idea of juxtaposing the music with the image to enhance a scene. The score for MAD GOD stumbles into that category more often than not for most viewers I suspect.

“At early screenings, I noticed people being completely freaked out by, and

sometimes fleeing the theater during scenes I found beautiful and whimsical”

I’ve been asked what kind of direction Phil gave. As I’ve alluded to, the answer is: Vague. Big-picture almost exclusively. I learned early that Phil’s style of directing is to stay out of the way of the creatives he’s chosen and trusts. He deliberately set up an environment, a framework that allowed for, and almost demanded maximum creative expansion from everyone involved. For whatever reason, that first demo earned me access to that framework. I remember once Phil gently shushing someone from the production when they tried to voice a small suggestion about what the music for one of the scenes could be, saying, “No direction”.

During the first year or so after I signed on it became clear that MAD GOD would need a proper theatrical audio mix, rather than just my “score-effects”. Bay Area sound designer Richard Beggs (Apocalypse Now, Lost In Translation, Harry Potter, and on and on…look him up), who Phil and I knew from working on Alex Cox’s films (him again!), agreed to have a look at the rough cut, and with little hesitation said flatly, “I’m interested”. It should be pointed out that MAD GOD was always sort of a side-project-of-love for everyone involved. No one was expecting to be paid, so it was a wonderful surprise when Richard agreed to do the sound. The technical knowledge and experience he brings to a film is invaluable, but it’s his unique conceptual slant on the role that sound design plays in Film that makes him an artist in the formal sense of the word – and also a perfect fit for MAD GOD it turned out. Richard’s sound design on MAD GOD is absolutely inspired. A masterpiece within a masterpiece it could be said. Not for one second during the long process of making MAD GOD did I take for granted, or not appreciate what a gift it was to be collaborating with these two luminaries of their respective fields.

I’d had the pleasure of working with Richard on several projects before this, those experiences being among the best I’ve had working on films. However, when Richard started in I wasn’t sure if the atmospheric, sound-designy approach staked out by the music at that stage would annoy him or get in his way, but it did neither. He welcomed it and encouraged me to do more, influencing the rest of the score considerably. I ended up working more closely with Richard on MAD GOD than I ever had with a sound designer. On most films it isn’t practical for the composer to work to anything resembling the finished sound effects track – leaving both sound designer and composer to guess at what one another are up to until very late in the process. But Richard allowed me generous access to hear what he was doing as things developed. This sort of back-and-forth affected the music directly. We routinely discussed ways to work together to enhance the piece and/or things we could do to stay out of each other’s way sonically. Given Phil’s hands-off style Richard often ended up hearing and incorporating the score into the mix long before Phil heard it.

“So protracted was the scoring process that not only did my aesthetic as a composer (and a human) evolve, so too did the tools. The synthesizers, workstations and other music tech the score was organized around changed considerably over the span”

There were lots of reasons why MAD GOD took so glacially long to complete (30+ years for Phil. 12 for me). The biggest chunk of time being the period when Phil set the project aside before the TIPPETT STUDIO people exhumed it. Then, as I mentioned, it was mostly a side project worked on in between everyone’s “day jobs”. It was also, of course, mainly a stop-motion project of incredible detail and craftsmanship, which had obvious built-in time constraints. But from the time I was around the main hold ups, if you want to call them that, seemed to be that each time the film neared completion Phil’s brain would gush another deluge of ideas – ideas we were always excited to run with. That first MAD GOD study I did demos for actually started, ended and had an arc, albeit a much shorter one, very much like the finished film, but Phil’s imagination kept manufacturing fresh, moist, wonderfully deranged schemes to “open up” the film, as he put it (essentially inserting scenes into the timeline, as opposed to extending it). With a talented and inspired crew on board Phil was free to expand the piece, and expand it more. As time consuming as the changes were, each one brought MAD GOD closer to the vision Phil had started out to realize in the early 90’s.

This ever lengthening, moving-target format had its own set of challenges for the music. It meant ripping apart and expanding cues I had composed, and that Phil had approved years earlier, that we had all become attached to, without losing their vibe. I also had to make sure that the established musical themes did their job of maintaining continuity without sounding repetitious once it was all done. As many may know, MAD GOD was first completed as chapters, being released every few years (I started the first chapter in 2009, the last, around 2019), so there would be years between working on scenes that would be only a few minutes apart once the chapters were strung together into the feature length version. Keeping a sense of the entire film’s score in my mind with such large breaks in the process required some vigilance.

So protracted was the scoring process that not only did my aesthetic as a composer (and a human) evolve, so too did the tools. The synthesizers, workstations and other music tech the score was organized around changed considerably over the span. A lot of the decisions I made in 09 I wouldn’t make today (2022). Fortunately, I must have been at least semi-aware of MAD GOD’s out-of-time quality when I started and didn’t employ too many of 2009’s trending film-scoring formulas or “cutting-edge” synth sounds* that would date the score. Towards the end of the process of completing MAD GOD there was a window of time where I could have gone back and updated the music with the latest sounds to de rigueur, but made a deliberate decision to let my choices over the years stand as a record-of-the-time. I made some late changes to the mixes, but mostly left any 09isms to fend for themselves.

“No one was sure how it would land with the outside world. It wasn’t until MAD GOD’s premiere at the Locarno Film Festival (Switzerland), did I realize that the film could very well be destined for a place in film history”

As lengthy as the process was I don’t think anyone wanted it to end. Phil said he was glad it was over, but I believe if MAD GOD hadn’t been accepted to film festivals, and subsequently found distribution, he would have just kept going and going, and all of us along with him.

Whereas I and everyone who poured themselves into the project are ecstatic and proud of the outcome, MAD GOD is not, to put it mildly, a normal film. No one was sure how it would land with the outside world. It wasn’t until it’s premiere at the Locarno Film Festival (Switzerland), did I realize that the film could very well be destined for a place in film history. In many ways I saw the film for the first time at that screening. There were still the requisite walk-outs even at the premiere, but something about seeing the film in that theater with a fresh, uninitiated audience made me recognize in a material way what a work of art Phil had created.

The response at Locarno and elsewhere was enormously, almost eerily positive. The wave of recognition visibly fazed the mostly unfazeable Phil Tippett, and I again took notice of my incredible fortune of wandering into, and sustaining orbit around him and the MAD GOD team.

As validating as the response was, I can honestly say that even if the film had crashed and burned it wouldn’t have mattered to me one bit. MAD GOD is a rare work of artistic purity. An uncompromised outpouring of creativity directly from the heart and mind of a visionary. It’s the kind of experience a film composer can only dream about being involved with. The kind of experience I was after when I began composing music for film.

_dan wool

MAD GOD Music Tools

Prominent Musical Instruments

- ● Prepared Acoustic Guitar (Epiphone D-145)

- ● Acoustic Guitar (1939 K Musical Instrument “Parlor Guitar”)

- ● Hoffman Piano Company Upright “Tack” Piano

- ● Kanstul Student Trumpet

- ● Johnson Ukelele

- ● Broken Hohner Melodica

- ● Really Nice Pawnshop Kalimba

- ● Bass (Gary Brown’s Yellow Fender P-Bass/Jazz Bass Creation)

- ● Miscellaneous Toy Instruments, Drums, Appliances and Junk-Percussion, Some Vegetables

Hardware Synths

- ● SC Prophet 600

- ● DSI Prophet 08

- ● DeepMind 12

- ● Access Virus b

- ● MOOG Theremin

- ● Roland JD-1080

- ● Kurzweil K2000

- ● Ensoniq ESQ-1

Prominent Software Synths

- ● Spectrasonics Atmosphere

- ● Spectrasonics Omnisphere (versions 1 – 2.5)

- ● NI Kontakt

- ● NI Reaktor

- ● MOTU MachFive

- ● UVI Falcon

- ● GeForce M-Tron/Pro

- ● Modartt Pianoteq

- ● Synthogy Ivory

- ● EastWest Play

- ● Orchestral Tools SINE

- ● Vienna Ensemble Pro

Prominent Software Instrument Libraries

- ● CineSamples

- ● Symphobia I

- ● Not many Spitfire libraries for some reason

Outboard Processing

- ● Empirical Labs FATSO Jr

- ● Roland DEP-5

- ● Ensoniq DP/4

- ● Roland RE-201 Space Echo

- ● Music Man 210-130 Guitar Amp (re-amp)

Prominent Software Processing

- ● Ina-GRM – Misc

- ● SoundToys – Misc

- ● UA Plugins – Misc

- ● Audiority – GrainSpace

- ● FabFilter – Misc

- ● Zynaptiq – Adaptiverb

- ● Rast Sound – Transformer

- ● Wavesfactory – TrackSpacer

- ● Eventide – H3000

- ● UVI – Sparkverb

Digital Audio Workstation

- ● MOTU Digital Performer (versions 6 – 11)

2024 Email interview with Juno Williams-Mitchell for the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute studying Communication, Media, and Design

WHAT NON-MUSIC MEDIA INFLUENCED THE SOUNDTRACK OF MAD GOD?

Theatrical sound-design would be the obvious one. A lot of the music in MAD GOD is more like tonal sound-design than musical composition. When I first started working on the film there wasn’t a sound designer involved so the compositions were created to work both as score and sound design. By the time there was a sound designer on board the tone of the music had been established, and I kept that approach for the rest of the score.

I definitely took cues from abstract expressionist and color field paintings from artists like Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko etc. Those artists famously used dense layers of pigments to create depth and complexity to otherwise rudimentary forms. The score for MAD GOD is not complicated musically. However it is often intricately and deeply layered.

HOW DO THE VISUALS OF STOP MOTION VS. LIVE ACTION INFLUENCE THE SCORING? IN GENERAL, IS SCORING ANIMATION MUCH DIFFERENT THAN LIVE ACTION?

Traditionally stop-motion and animation scoring is the most detailed type of scoring work there is, with attention given to every movement and story-beat on the screen. Music for live action projects, in general, are much more zoomed out, and will play to the overall story and/or subtext of the film (of course contemporary animation and stop-motion movies can, and often do, all of the above masterfully – think Pixar and Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio).

While it is a stop-motion film, anyone who has seen MAD GOD will agree that it defies and deliberately avoids category and genre. So too, does the score I think. From the outset MAD GOD was meant to be an ambient art piece, with a loose anti-narrative structure that would obligate viewers to create their own story from the images they were seeing. The score is meant to help facilitate that experience by remaining neutral, with the use of counterpoint. The score is weighty but mostly soothing compared to the dark imagery. I think this creates balance and a space for viewers’ imaginations to expand into.

THE FILM BEGINS FOLLOWING A SINGLE ASSASSIN CHARACTER, WITH THE AUDIENCE BELIEVING HIM A ONE-OF-ONE LONE EXPLORER. WHEN HIS JOURNEY IS QUICKLY ENDED AND IT IS REVEALED THAT HE IS ONE OF MANY, DOES THE INTENTION BEHIND THE SECOND ASSASSIN’S SONIC CHARACTERIZATION CHANGE?

Hey, that’s not a bad idea! I should have done that! But, no. The assassin’s journey in my mind’s story doesn’t end. I think the approach I stumbled into helps place the assassin outside of linear time (within circular time perhaps). Not acknowledging the one-of-many revelation with the score, as if it were a given, probably works better.

THE SCORE IS OFTEN DESCRIBED AS “HAUNTINGLY BEAUTIFUL,” IN NO SMALL PART DUE TO THE USE OF ACOUSTIC GUITAR AND A MUSIC BOX OR HARPSICHORD. DID THESE STAND OUT AS OBVIOUS CHOICES FOR THE INSTRUMENTATION, OR DID IT TAKE MULTIPLE ATTEMPTS TO FIND THE RIGHT SOUND? IF THE LATTER, WHAT INSTRUMENTS AND SOUNDS MIGHT YOU HAVE TESTED AND REJECTED?

It’s always nice to hear the score characterized in those terms. The instrumentation choices were more than obvious. Like much of the composition, those choices were nearly automatic. A simple Rorschach response to the visuals using tools I had on hand. The very first super rough and spontaneous demo I sent to Phil went over so well that I stuck with that spontaneous, instinctual composition approach for the rest of the project. That first demo remains in the film exactly as I wrote and recorded it in 2010.